A slaughter calculated to terrify non-Muslims throughout Holland took place in Amsterdam on Tuesday morning, 2 November 2004.

While riding a bicycle to his film studio, Theo van Gogh, a distant relative of the renowned painter Vincent van Gogh, was gunned down by a bearded man in traditional Islamic clothing. The assailant, a Dutch-born man of Moroccan descent and a devout Muslim, was incensed by a short film that van Gogh had made about the oppression of women under Islam. As van Gogh lay mortally wounded, the young man repeatedly plunged a stabbing knife into his body, then slit his throat with a butcher’s knife. Finally, the killer took the first knife and stabbed a letter written in Arabic and Dutch to van Gogh’s chest.

The letter, which opened “In the name of Allah the kind, the merciful”, was addressed “to an infidel fundamentalist, Ayaan Hirsi Ali”. Sprinkled with quotes from the Koran, it claimed that Ayaan had offended Islam and it threatened her with slaughter in this life and torment in the next: “you have been constantly terrorising Muslims and Islam with your words. … This letter is Insha Allah an attempt at silencing your evil once and for all. … AYAAN HIRSI ALI YOU SHALL BREAK YOURSELF ON ISLAM! … There shall be no mercy for the unjust, only the sword raised at them. … I deem thee lost, O Holland. I deem thee lost, O Hirsi Ali …”*

The letter, which opened “In the name of Allah the kind, the merciful”, was addressed “to an infidel fundamentalist, Ayaan Hirsi Ali”. Sprinkled with quotes from the Koran, it claimed that Ayaan had offended Islam and it threatened her with slaughter in this life and torment in the next: “you have been constantly terrorising Muslims and Islam with your words. … This letter is Insha Allah an attempt at silencing your evil once and for all. … AYAAN HIRSI ALI YOU SHALL BREAK YOURSELF ON ISLAM! … There shall be no mercy for the unjust, only the sword raised at them. … I deem thee lost, O Holland. I deem thee lost, O Hirsi Ali …”*

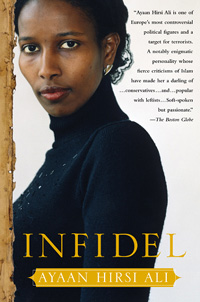

Ayaan Hirsi Ali was the target of the killer’s wrath because, among other things, she wrote the script for Theo van Gogh’s film, Submission. She has since written other works critical of Islam, the latest being her internationally best-selling autobiography, Infidel (New York: Free Press, 2007).

Infidel opens and closes with references to van Gogh and its penultimate chapter details how his murder has affected Ayaan herself. But such is the nature of Ayaan’s life that van Gogh’s murder is merely one of many dramatic and horrific events recorded in the pages of her autobiography, which traces her life from childhood to adulthood, from genital mutilation to forced marriage, from Somalia to Holland, and from Islam to apostasy.

Ayaan’s account of her upbringing is both fascinating and ghastly. She was born in Somalia in 1969 to devout Muslim parents who belonged to an important Somali clan. Due to his political activities and his other wives, Ayaan’s father was rarely home, so her mother and grandmother were responsible for her (and her siblings’) upbringing.

From the outset Ayaan’s life was governed by the strictures and superstitions of Islam and the obligations and expectations of her clan. Her mother and grandmother drummed into her the Islamic and clannish concepts of honour and submission:

“In Somalia, little children learn quickly to be alert to betrayal. Things are not always what they seem; even a small slip can be fatal. The moral of every one of my grandmother’s stories rested on our honor. We must be strong, clever, suspicious; we must obey the rules of the clan.

“Suspicion is good, especially for a girl. For girls can be taken, or they may yield. And if a girl’s virginity is despoiled, she not only obliterates her own honor, she also damages the honor of her father, uncles, brothers, male cousins. There is nothing worse than to be the agent of such catastrophe.” (p.6)

When she was five years old, Ayaan was “circumcised”. Although female genital mutilation was (and is) standard practice in Somalia, as in other Muslim countries across Africa and the Middle East, her father was opposed to it. But her mother and grandmother arranged to have her and her sister, Haweya, “circumcised” in his absence:

“She [Grandma] caught hold of me and gripped my upper body … Two other women held my legs apart. The man, who was probably an itinerant traditional circumciser from the blacksmith clan, picked up a pair of scissors. With the other hand, he caught hold of the place between my legs …

“Then the scissors went down between my legs and the man cut off my inner labia and clitoris. I heard it, like a butcher snipping the fat off a piece of meat. A piercing pain shot up between my legs, indescribable, and I howled. Then came the sewing: the long, blunt needle clumsily pushed into my bleeding outer labia …

“I must have fallen asleep, for it wasn’t until much later that day that I realized that my legs had been tied together, to prevent me from moving to facilitate the formation of a scar.” (pp. 32)

Female genital mutilation makes for misery on the wedding night, as Ayaan records later in the book. A friend who was married when she was just fourteen reported

“what it was like when Abdallah [her husband] had first tried to penetrate her after they were married: pushing his way into her, trying to tear open the scar between her legs, how much it had hurt. She said Abdallah had wanted to cut her open with a knife, because she was sewn so tight … She described him holding the knife in his hand while she screamed and begged him not to—and I suppose he felt pity for that poor fourteen-year-old child, because he agreed to take her to the hospital to be cut.” (pp.90)

Some time after she had been made “pure” through the mutilation of her genitals, in 1978, Ayaan relocated from Somalia to Saudi Arabia. This nation was her mother’s choice: “My mother didn’t want to move to Ethiopia, because Ethiopians were Christians: unbelievers. Saudi Arabia was God’s country, the homeland of the Prophet Muhammad. A truly Muslim country, it was resonant with Allah …” (p.37)

Yes, Saudi Arabia is a faithful Muslim country, a model Islamic society. And that is what makes it such a barbarous place. For the closer one gets to the life and teaching of the Prophet Muhammad, the closer one gets to bigotry and brutality, as Ayaan soon found out:

“In Somalia we had been Muslims, but our Islam was diluted, relaxed about regular praying, mixed up with more ancient beliefs. Now our mother began insisting that we pray when the mosques called, five times each day. …

“In Somalia, both school and Quran school had been mixed (boys and girls); here everything was segregated. … All the girls at madrassha were white; I thought of them as white, and myself, for the first time, as black. They called Haweya and I Abid, which means slaves. …

“Everything in Saudi Arabia was about sin. You weren’t naughty; you were sinful. You weren’t clean; you were pure. The word haram, forbidden, was something we heard every day. …

“My mother found comfort in the vastness and beauty of the Grand Mosque …

“But as soon as we left the mosque, Saudi Arabia meant intense heat and filth and cruelty.People had their heads cut off in public squares. Adults spoke of it. It was a normal, routine thing: after the Friday noon prayer you could go home for lunch, or you could go and watch the executions. Hands were cut off. Men were flogged. Women were stoned. …”

“Some of the Saudi women in our neighbourhood were regularly beaten by their husbands. You could hear them at night. Their screams resounded across the courtyards: “No! Please! By Allah!” …

“When my mother went shopping without a male driver or spouse to act as guardian, grocers wouldn’t attend to her. … None of the Saudi women we knew went out in the street alone. They couldn’t: their husbands locked their front doors when they left their homes. …

“Some time after we moved to Riyadh we started school … we learned how good Muslim girls should behave: what to say when we sneezed; on which side we should begin to sleep, and to what position it was permissible to move during sleep; with which foot to step into the toilet, and in what posture to sit. The teacher was an Egyptian woman, and she used to beat me. … When she hit me with a ruler she called me Aswad Abda: black slave-girl. I hated Saudi Arabia.” (pp.42-43, 47-49)

In 1979, Ayaan’s family shifted from Saudi Arabia to Ethiopia to rejoin her father; and a year later her father sent them on to Nairobi.

Although Kenya was a non-Islamic country (and therefore despised by Ayaan’s mother), the influence of Islam was strong. As they entered their adolescent years in Kenya, Ayaan began to read English-language novels and “An entire world of Western ideas began to take shape. … All these books, even the trashy ones, carried with them ideas—races were equal, women were equal to men—and concepts of freedom, struggle, and adventure that were new to me.” (p.69) Ayaan especially liked romance novels, whether they were “good books” like WutheringHeights or merely “trashy soap opera[s]”. She found that “buried in all of these books was a message: women had a choice.” (p.79) That is, women apart from Islam had a choice.

In stark contrast to the women in the Western romantic novels, the teenage girls with whom Ayaan attended Muslim Girls’ Secondary School had no choice in anything, let alone in matters of love and romance:

“One after another, girls began announcing that they were leaving school to get married. … One girl was forced to marry her uncle’s son, her cousin. A fifteen-year-old Yemeni classmate told us she had just been betrothed to a much older man; she wasn’t happy about it, but, she added, “at least it’s not as bad as for my sister—she was twelve.”” (pp.77-78)

Interestingly, while Ayaan was drawn, through the books she was reading, to the notion of freedom and equality for women, she was also drawn deeper into Islam. She came under the influence of Sister Aziza, an Arab Kenyan, who was herself a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, “a huge evangelical sect backed massively by Saudi Arabian oil wealth and Iranian martyr propaganda.” (p.88) In imitation of Sister Aziza, Ayaan began to wear the hidjab, “a huge black cloak” that fell to her toes, and “a black scarf” over her hair and shoulders.

Yet even as she grew more devout, Ayaan began to doubt: how could Islam be true when because of it women were so downtrodden?

One day, when she was seventeen, Ayaan dared to question a Muslim Brotherhood teacher (ma’alim) who was telling the mothers and teenage girls who had gathered to hear him that they owed their husbands absolute obedience. “If we disobeyed them, they could beat us. We must be sexually available at any time outside our periods, ‘even on the saddle of a camel,’ as the hadith says.” (p.103) Concluding that “this wasn’t any kind of loving partnership, or mutual giving”, Ayaan asked, “Must our husbands obey us, too?”

When the irate teacher told her, “You may not question Allah’s word!”, Ayaan began to question in her mind whether Allah’s word really said the things the teacher claimed it said. The flaw could not be in the Koran, she reasoned, so it must be in the way the teacher was representing it:

“I thought that perhaps [the teacher] was translating the Quran poorly: Surely Allah could not have said that men should beat their wives when they were disobedient? Surely a woman’s statement in court should be worth the same as a man’s? I told myself, ‘None of these people understands that the real Quran is about true equality. The Quran is higher and better than these men [teachers].’

I bought my own English edition of the Quran and read it so I could understand it better. But I found that everything [the teacher] had said was in there. Women should obey their husbands. Women were worth half a man. Infidels should be killed.” (p.104)

When she was 22, in 1992, Ayaan was given in marriage to a distant cousin whom she had never met. Her father arranged the marriage despite her objections and proceeded with it despite her refusal to attend the wedding:

“The day of my wedding I did what I always did every day. I dressed normally and did my chores. I was in denial. I knew that over at Farah Goure’s house there was a qali [Islamic marriage celebrant] registering my union with Osman Moussa before my father and Mahad and a crowd of other men. … Neither my presence nor my signature was required for the Islamic ceremony.” (p.176)

After the wedding, Ayaan’s husband left Kenya for Canada, where he had settled some years earlier, and she was supposed to follow him there. Her father sent her to Germany to await the issuance of a Canadian visa. But soon after arriving in Germany, she caught a train to Holland intending to apply for asylum.

“It was Friday, July 24, 1992, when I stepped on the train. Every year I think of it. I see it as my real birthday: the birth of me as a person, making decisions about my life on my own. I was not running away from Islam, or to democracy. I didn’t have any big ideas then. I was just a young girl and wanted some way to be me; so I bolted into the unknown.” (p.188)